The Prince of Wales Visit 1921

Lots of things happened in 1921, good and bad. Insulin was discovered, the communist party was formed in China, Hitler became the leader of the Nazi party, Einstein was nominated for the Nobel prize, and so on and so forth. In British India, KR Narayanan and Satyajit Ray were born, Tagore inaugurated his Viswabharathi university, Gandhiji’s noncooperation movement supported by the united front shook up the administration and the English bigwigs in the UK were becoming a nervous lot. What alarmed them however was the Moplah rebellion in Malabar which fanning out in the south, alienating the Muslims and the Hindus in an otherwise laidback region. The communal overtones needed to be handled carefully and differently from the methods which had culminated in a tragedy at Amritsar just two years earlier.

1919 and 1920 were bad years following the massacre at

Amritsar and throughout 1920, India continued to be in a serious state of unrest.

The Non-Cooperation movement linked up with the Khilafat movement dear to the

Muslims, and as days went by, the latter became increasingly turbulent; they

wanted to cast their loyalty to the Turkish Sultan, their Caliph or Khalifa, and

not the King-Emperor. Other issues such as the poor monsoon, a threat of famine

etc. were making both the administrators and the common man feel that matters

were getting out of control, that Government authority was breaking down.

Strikes followed in Bombay, Ahmedabad and Kanpur and the earlier feeling that Indian

support for the WW1 would result in some good, were soon negated.

As the police proved to be ineffectual and the Khilafat

undertones continued to feed the frenzy in Malabar, martial law had to be

declared and the army was brought in from Bangalore and Burma, in order to deal

with the unrest and violence. The military took care of the rioters and rebels

ruthlessly, and in the intervening days, as morals were shed and violence

reigned supreme, members of all communities suffered huge losses in life and

property, leaving the Malabar administration in utter disarray. Slowly things started

to get back on even keel, but religious amity which was once prevalent in the

region got replaced by hostile animosity, and polarized communities took to

avoiding each other.

But there was an important event, planned a long time ago,

which was the visit of the Prince of Wales to India, underway. The British had

come to an agreement with some princes that the event would not be overshadowed

by dissent and violence, though Gandhiji and the Congress hesitated from making

such a commitment. Barbara N. Ramusack’s book on the Princes of India, reveals

to us that things had not improved in 1920 and the princes had suggested that Edward

dole out some boons if he were to be seen as populist.

The intent of these tours through the royal domains was of

course to instill awe and respect for the distant monarch, through the visit of

his representative. It had to have the pomp and monarchical splendor if only

for the people to always remember fondly of the day when they saw a future

king, who traveled thus far to see them! Well, it was actually a little bit

more, since Edward was supposed to inaugurate the imperial legislative assembly

as well as the chamber of princes and stamp a royal approval on new administrative

processes in India. The tour which was planned for 1920 was postponed due to

royal fatigue, as well as the revolts in India. The inauguration was therefore done

by the Duke of Connaught and Edward rested. But as Edward rested royally, India

was convulsed with rebellions, and it was a dissenting country which awaited

him, with the rumblings under the surface picking up in frequency, and tending

towards something much bigger. Cancellation would not do, for Gandhi would add it

as a feather on his cap! From the British viewpoint the visit was on, the

Prince of Wales’s trip would be of some value during the deepening

confrontation between the Indian nationalists and the British Raj, or so they

felt.

The logistics had been carefully prepared as a PR event

replete with glowing tributes and a lot of handclaps, and Edward‘s route was to

cover many cities and towns which were trouble-free and friendly to the crown. Would

that event go well or would other events mess it up even more? Well, that is

what this story is all about, the happenings in Bombay prior to, during and

after the arrival of Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David - the stylish

Prince of Wales.

This is also a story where we find a normally placid lot,

the Parsees and the Anglo Indians of Bombay, pitted against the other

communities of Bombay in a short, but bloody and violent riot which later came

to be known as the Prince of Wales riot. It occurred between 17th and

20th November 1921, coinciding with the arrival of the Prince of

Wales, the future King Edward VIII to the metropolis.

The prince’s steamship was to arrive grandly in Bombay and

the man would walk through the Gateway of India, which was still under

construction, a symbol of "conquest and colonization" commemorating

British colonial legacy. A trip that would cover some 40,000 miles in 8 months

was underway. While most of the sailing was in the frigate Renown, the Dufferin

would take him on the shorter legs to Burma and Calcutta. For the night time

land trips, three trains were placed at his disposal, so also camels, elephants, and palanquins for his royal comfort on rough terrains!

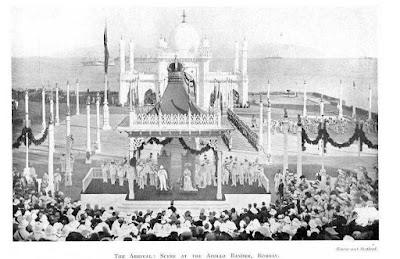

On Nov 17th, he arrived in Bombay. The official record explains the arrival in formal terms – His barge swung alongside the Apollo Bandar, where the Viceroy awaited him, and he passed through the imposing Gateway of India—a lofty, unfinished arch at the waterside— to a crowded amphitheater beyond. Here, in the presence of a glittering assemblage, he stood under a silken canopy, on a carpet of cloth of gold, and read the King's Message. The state procession, with its escort of scarlet cavalry, carried him through five miles of beflagged streets from the modern European city into a residential quarter fully mobilized in his honour, and thence to Government House at the end of Malabar Point.

The obvious sincerity of the welcome on the route was in

striking contrast with the disaffection revealed elsewhere. The rioting in the

bazaars, that necessitated the employment of armored cars, never extended

beyond the limits of the Indian quarter. The Prince heard no discordant note in

the rejoicing, saw no sign of hostility in the faces around him.

This was true not only of his first journey through

Bombay, but of all other appearances there in public as well. He went about

freely outside the native city, fulfilling a program that was in no wise

affected by the pressure of political agitators. He walked through a dense

throng of Indians on the maidan—a great open space skirting the European

quarter—with no more apparent precautions than might be taken to secure him

elbow-room in a London crowd. He visited the University, the Seamen's

Institute, and the Yacht Club; presented colors to the 7th Rajput’s on the Maidan

in the presence of a vast crowd, and witnessed a fine naval and military

pageant which followed the final cricket match of the quadrangular tournament

between teams representing the Presidency and the Parsees.

The president of the Bombay Corporation, a Bombay once an

area gifted many years ago by the Portuguese as a dowry to the Portuguese bride

marrying a British Prince, grandly announced that they regarded the throne of

England as the enduring symbol of the principles of equity, justice and

liberty.

But what we failed to see in these words was that the

discontent which had been brewing for months had actually spilled out into a

riot just after the speeches by the Prince had been made and the dignitaries

left the podium. Let’s take a look at the day, but before that, a little

introduction to the Parsee and the Anglo-Indian population in Bombay, two of

the groups friendly to the British monarchy.

With the advent of British power in India better and

brighter days dawned for the Parsees. The British encouraged the enterprising

lot to settle down at Bombay, gave them the land, and they quickly became a

bridge between the indigenous peoples and the ruling British, getting immensely

prosperous, along the way. Shipbuilding and trading established them as a

favorite go-between in the British scheme of things and the lucrative opium

trade with China, got them the steady volumes to build upon and prosper. After

the Suez Canal was opened in 1869, Bombay incidentally had become India’s

principal port. In addition to opium trading and shipbuilding, the Parsees

controlled the many cotton mills of Bombay, cotton being a product in great

demand in the west, particularly America. Soon they branched out into other

industries, transport and whatnot, establishing themselves at the top of the

hierarchy of the Indian peoples. But there was one problem, one which comes

from wealth and education, for the educated Parsee also wished to be regarded

as being separate from the other communities of India, especially so since they

were westernized in their habits, they felt they were more British than Indian. After all, they wore suits and western outfits, ate the British way, played the

piano, played cricket, spoke fluent English, wore custom shoes, carried

themselves proudly, and even attempted to reform the lower masses! Well, one

thing was clear - all this was soon going to create more harm than good, as

wise men muttered.

Quite a few Parsees were firmly behind Gandhi’s

noncooperation movement. Some though involved with the Congress, retained a

certain amount of reverence for the British, while some others trod the main

course, with Gandhiji. The Indian leader courted this affluent community early,

in his efforts to confront the English, for they not only held the purse

strings but also had the ear of the British. Gandhiji nevertheless, always held genuine respect for this community with whom he had dealt while in South

Africa. He kept exhorting all of them to join the Swaraj movement, but somewhere

along the way, a number of not so nationalistic Parsees got alienated from the

Indian leader, and his ideology.

Many from the upper echelon Parsees kept aloof from the

popular anti-British movements and even stated their distaste in the press, for

they also feared an India of the future, governed by strident religious

communities such as the Hindu and the Muslim, fearing they would be sidelined

as an 80,000 strong micro minority. Most of all, they did not want to support

something which threatened their very livelihood – the mills, the offices where

they worked, the legal and financial sectors, all of which would be soon

brought to a standstill by these movements. Another huge threat was the

Gandhiji ban on alcohol sales, for the Parsees not only loved his peg or two but

also owned most of the liquor shops in Bombay. They also rented and controlled

the palm farms down south which produced the toddy and arrack, and all that

business would be bankrupted if they supported prohibition. So, while some

moved with Gandhiji, others remained wary and knew that this all the

frustration and pent-up emotion of the community was going to erupt, one day.

The Anglo Indians were also a community left in a quandary,

for the nation seemed to have no place for them, be it on the British side who

treated them with disdain, or the nationalists who mistrusted their loyalties.

They had always thrown their lot with the British and had little connection

with the nationalists or the swaraj movements, barring a few rare individuals.

The British seeing this did think of creating some safe havens for them, but

with the jobs available only in cities, these enclaves such as Whitefield and Mccluskiegunj

were only of interest to wealthy retirees. In Bombay, they congregated in

Colaba, Byculla, Bandra, Mahim and worked for the railways, police, air force,

navy and so on. Anglo-Indians also participated actively in the armed forces of

the Empire, military and police and some muttered that the Government was not

fully utilizing their services. In fact, many were anti Gandhi, right through

the movement.

At 1030 AM, Gandhiji lit the bonfire, and the flames swept

upwards as suits and caps, and many objects of apparel with a western feel were

consigned to the flames. Sir Jejeebhoy read out Bombay’s welcome while a group

of Parsee girls danced a Garba for the prince. After the event, the Parsees and

the Christians boarded a few trams and other vehicles heading home to the

suburbs. What they had not planned for was the hostile reception planned by the

rioters, mainly workers from the Elphinstone mills, waiting just outside the

police ring. The mob attacked the trams, assaulted all western attire clad

Parsees, Anglo Indians, as well as the few Europeans, resulting in utter chaos.

They continued with attacks on liquor shops, smashed trams and killed a few

policemen.

Naresh Fernandez explains in his fine book City Adrift - Many

of those lessons were learned during the Non-Cooperation Movement, launched in

1920. Among its cornerstones was the idea of swadeshi—self-reliance, with its

attendant strategy of boycotting foreign goods. As was to be expected, the

campaign, which had direct impact on Bombay’s wallet, divided opinion in

India’s industrial capital. While mill workers and the Gujarati and Marwari

traders in the city’s cloth markets were keen supporters of the nationalist

cause, mill owners, who often needed to import machinery, tended to be loyal to

the British. Among the exceptions was Umar Sobani, the owner of Elphinstone

Mill. On 31 July 1921, as 12,000 people gathered in the compound of his

factory, Sobani stepped forward to set fire to a huge pile of foreign-made

clothes. Volunteers had gone door to door collecting garments for the bonfire.

By one account, the clothes tossed into the bonfire were worth Rs 30,000. The

bonfires were lit again on 17 November, the day that the Prince of Wales

arrived in Bombay to tour the empire he would later inherit. Gandhi’s followers

wanted the flames to be high enough for the prince to see as he landed at

Apollo Bunder, far across town. But the day ended in violence.

The mob fury continued for the next five days as the Parsees

and Anglo Indians retaliated. Parsees, Muslims, Jews, Christians, Anglo

Indians, mill laborers, all continued with rioting in their own areas, fighting

with one other as the attacks became communal in nature. The Parsees attacked

anybody wearing a Gandhi cap and the Anglo Indians as well as the Europeans retaliated

with ammunition they possessed. There were also rumors that there were some

British CID hands behind many of the events, those police wanting to teach

Gandhi a lesson and expose him as the one who instigated these riots. It was

also felt that the police in general supported the Parsee, Christian and the

Jewish sides.

Gandhiji felt that the Parsees had been wronged and castigated the warring lot thus – Hindus and Mussulmans will be unworthy of freedom if they do not defend them and their honor with their lives.’ It was therefore incumbent upon the Hindus and Muslims of Bombay to express their ‘full and free repentance’; otherwise, he could not ‘face again the appealing eyes of Parsi men and women’. He also added for the first time that defensive violence may be acceptable by stating - Certainly the Parsee Mavalis are less to blame and ‘I can excuse the aggrieved Parsees and Christians’. After four terrible days, things calmed down. Gandhiji broke his fasting on 22nd, and spoke again, after the mobs slowly dispersed - exhorting his followers and referring to Parsees, Christians and Jews, he stated, ‘We must go out of our way to be friendly to them and to serve and help them, above all to protect them from harm from ourselves.’

At least 58 people lost their lives, including three

Europeans, two Parsis, one American and five police officers while many

hundreds were injured. William Francis Doherty, an American engineer was one of

the unfortunate victims of this riot and his wife Annette swore an affidavit in

an LA court that she was requested by Sarojini Naidu and Mahatma Gandhi to

remain quiet about the event. Of the many hundred liquor shops, 135 were

damaged and four were completely destroyed. The government prosecuted over 400

suspects, eventually hanging two convicted rioters, transporting two others for

life, and sentencing over a hundred others to rigorous imprisonment. Those five

days proved to be a delicate balancing act for everybody involved, the police,

the congress, Bombay’s leading citizens and of course the Prince’s entourage, as

the city burned.

Let’s take up the story of the man of the moment, Edward

VIII. What did he do? After watching a cricket match and the festivities

planned for him, he holed up in the Government house at Malabar hill, as the

city writhed. He laid a foundation stone on the Shivaji memorial at Poona,

moved on to Baroda and Udaipur, then traveled to Calcutta to receive an honorary

doctorate opened the Victoria Memorial and moved on to Madras for four days where

he got a fine Dravidian welcome and faced some revolt, while Dickie Mountbatten

- his ADC (later viceroy) recorded the details of the sporadic riots, shuttered

shops, the many children who lined the roads, etc. Then he visited Mysore and

Hyderabad, followed by Bhopal and Gwalior, to culminate with the Delhi Durbar

in Feb 1922. Jullundur and Karachi followed after which he sailed to Ceylon in

March 1922. Four months of waste, many dead game animals shot by him and his

entourage, many hundreds of thousands of pounds spent on this wasteful trip,

well, then again those were the days of the Raj!

While the press applauded his visit where the Prince came

and conquered, he himself muttered that he had learned little, something we can

agree with. Polo, pig-sticking, boar hunting, tiger shooting, elephant shikars, and racing doubtless kept him rather busy. Well, the dapper prince certainly came,

saw and went, doing absolutely nothing of substance. In Bombay, Gandhian

nationalists lay claim to the Esplanade Maidan in South Bombay, a vast open

space, a symbolic center of the British establishment, was renamed Azad Maidan later

to become the stage for nationalist defiance and protest.

References

Beyond Hindu–Muslim unity: Gandhi, the Parsis and the Prince of Wales Riots of 1921 - Dinyar Patel

The Princes of India in the Twilight of Empire: Dissolution of a Patron-client System, 1914-1939 - Barbara N. Ramusack

Gandhi: Pan-Islamism, Imperialism and Nationalism in India - By B.R. Nanda

The Prince of Wales – Eastern Book

City Adrift - Naresh Fernandes

4 comments:

What an history.

Looks like Indians get mislead very easily.

A very interesting read.

thanks Haddock

on the face of it, it was somewhat insignificant & got contained quickly, but it tells you quite a bit of the multifaceted situation those days!

thanks SW,

glad you enjoyed it

Post a Comment