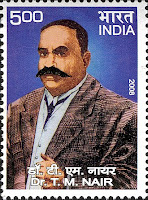

Doctor, Administrator, Journalist, Social reformer, and Politician (1868-1919)

This was a man who never had any qualms about taking on any

establishment, faction, or individual if he felt they were wrong. Hailing from

the Tharavath ancestral home in Palghat, he chose the field of medicine, became

a well-known doctor in Madras, then decided that social work was equally

important, got involved in all kinds of civic and social matters. During this

period, irked by the Brahmin stronghold on jobs and their control over the bureaucracy,

he took them on, starting what we know today as the Anti-Brahmin or Dravidian

movement, and later co-founding the Justice party. Alongside came the much

written about confrontation with Annie Besant and Leadbeater, but before he

could become an even more popular leader, he passed on, while visiting Britain,

in 1919. That was Dr. T.M. Nair.

In the British times, in the Madras presidency, a lot of

people made a beeline for Madras, its capital, leaving their traditional

occupations such as agriculture, to get educated and pick up a new trade, such

as medicine, engineering, law, or whatever. And there were a rare few who

ventured beyond, mainly to Britain. Most

of them rose to become noteworthy administrators and wrote their memoirs, some

did not. This portly, domineering, barrel-chested and heavy mustachioed doctor,

reminding you of a professional wrestler, was omnipresent in Madras during his

times, and when he talked (his tongue was even more mordant than VK Krishna

Menon’s) or wrote, people stopped what they were doing and took notice. That

was Dr. Tharavath Madhavan Nair, or simply TM Nair, the doctor from Malabar.

Strange is the fact that Nair died from complications of the very disease, he

was considered an expert on – namely, Diabetes!

Early on in his student days, he took to civic duties, he

was a member of various associations and societies. Mastery of the pen came

with his position as one of the editors of Edinburgh University Liberal's

magazine "The Student". He also spent a while in London as a Secretary

and later Vice-President of the London Indian Society which was led by Dadabhai

Naoroji. During a decade in Britain, he became what they called, ‘a thorough

gentlemen’ with poise and a great education.

The anglicized Malayali

Nair was quite adept at Sanskrit and Malayalam, but English

was his natural language, especially so after the British sojourn. Karunakaran

Menon explains an incident before Dr. Nair’s departure for England in 1889 when

“a few of us took a group photo ... A lady in England on seeing the photo

enquired whether he had been once in petticoats and on that he tore the photo

to pieces not to keep it any longer, as evidence of the garb in which he had

been at that time dressed.”. After his return from Britain, he spoke in

public only in English, was considered an anglophile and reputed to be the first

South Indian speaker who introduced the “modern style of eloquence" by

which it meant he had style, force, and humor, not just rambling on for hours using

flowery phrases and unintelligible words like many others did.

Nair the Doctor

As a doctor, Nair presented numerous papers and participated

in many committees, represented India on numerous occasions, chaired many groups,

and was considered to be the first to study diabetes and write extensively

about it. It is said that his book on Diabetes is still taught at some Indian

universities. His ENT clinic in Madras bustled with patients and Dr. Nair had a

lucrative practice. He was involved in the study of tropical diseases (Filaria,

Leprosy) while practicing in India and frequently collaborated with his counterparts

in Britain, often publishing the findings. As a member of the Municipal

Corporation representing Triplicane, he used to take a keen interest in public

health and often referred interesting cases to his counterparts abroad. According

to Deborah Brunton (Health, Disease, and Society in Europe, 1800-1930: A Source

Book) TM Nair endorsed wholly Western medicine, but was critical of the British

for not doing more to give – or allow- India the benefits of science and

sanitation.

Return to Madras, Journalism

Writing seems to have taken a grip of him, for we see his

involvement in the Kerala Patrika, a newspaper started by Kunhirama Menon

supporting the national movement (he used to contribute articles while in Britain)

and later in the Madras Standard, then under the editorship of Congressman G.

Parameshwaran Pillai. Pillai became editor of the Madras Standard in 1892 and

Nair’s friendship with Pillai perhaps influenced his championship for the

rights of the lower castes and the downtrodden.

Nair as Councilor of Triplicane

Nair decided to take a plunge into the socio-political scene

and was soon the councilor for Triplicane in the Madras Corporation, a position

he served from 1904-1916. He gave lectures on municipal governance in 1906 and

again in 1915, and in 1912 he was elected to the Madras Legislative Council.

The quality of potable water in Madras was a favorite

subject of his and he often took umbrage with FC Molony who headed the Madras

Corporation. Molony was responsible for

public water supply and Nair vehemently attacked the decision by Molony to

supply what was known derisively as ‘Molony’s mixture’ (Molony clarifies that

it was P Rajagopalachariar who coined the term) an adulterated mix of filtered

and unfiltered water (i.e., the terrible stuff) to create an unpopular derivative.

The working man’s friend

During the discussions around revising the Factory act, we

can see Dr. Nair, representing the Indian worker, working ceaselessly as a

member of the labor commission, issuing an oft-quoted and strongly critical

Minute of dissent in 1908 (Parliamentary Papers, Volume 74) focusing on the

medical as well as economical aspects. He complained about the poor air quality

in the mills and high humidity, irking their owners, and had no qualms in

stating that Indian employers fared worse (he however singles out Tata and Sons

as an exemplary employer) and treated their laborers badly. Nair’s opinions,

well backed up by evidence and strongly worded, were respected and taken

seriously by the British, throughout his life.

Nair’s minority report and dissent note was the basis behind

the final act of 1911. It resulted in many changes, securing a weekly holiday

for all factory workers, restricting working hours to eleven for women, a

mandatory hour and a half rest, prohibiting working women and children at

night, raising the working age of children, and restricting their work hours,

to name a few.

Antiseptic Magazine and Wartime work

Antiseptic, a monthly journal of medicine and surgery, the

first of its kind in India, edited by him appeared in May, 1904 with Dr. U Rama

Rao as its proprietor and manager. Later versions featured articles about

Diabetes and other subjects, which were of high quality, often picked up by

journals overseas. The magazine continued publication for almost 16 years.

TM Nair served on the hospital ship HS Madras (originally SS

Tanda a steamship owned by BI Steam navigation Company to transport Chinese

from Calcutta to the Far East) maintained with volunteer War funds during WW 1

as a full-time surgeon, and rendered medical service to wounded soldiers at

Mombasa, Zanzibar, the Persian Gulf, and Europe, until 1915, after which he

resigned and came back to Madras. His report on gunshot wounds is quite an

interesting read.

Nair, Annie Besant & Leadbeater

Though a medical journal, Nair used to slip political

articles into his Antiseptic magazine. Annie Besant had by this time, living in

Madras and anchoring the popular Theosophical society, started championing the

Home Rule for India. Her emphasis on the Brahmanical past of India, a base of

the Theosophy ideology, placed her as the main opponent of the Dravidians or

the non-Brahmins and started a massive political dispute. Natesan, Chettiar,

but mainly Dr. Nair, spearheaded the opposition’s response.

One of the articles Dr. Nair published was about child

abuse. Nair alleged that Besant’s associate Charles Webster Leadbeater imposed homosexual

tendencies on some of the boys in his care, under the guise of “initiating” rites.

Besant sued Nair in 1913, for defamation, but lost the case. Besant appealed to

the Privy court in Britain but lost again. The story, covering Besant, Leadbeater,

Narayanaih, his two sons (Jiddu Krishnamurthy the purported messiah, was one

who later became famous), is a long and sordid one. Nair covered much of it in

his Antiseptic magazine, later collated and published as a book. There was no

love lost between Besant and Nair and they fought each other ferociously, on

many fronts. One can assume that the home rule ideology met its end due to the

efforts of Dr. Nair and the justice party.

Anti-Brahmin agitations, Dravidian movement

Dr. Nair was a regular at the Indian National Congress gatherings

until 1916 starting as a volunteer, he even presided

over the North Arcot Congress conference at Chittoor in 1907. However, he

blamed it and the Brahmin lobby for his loss in a 1916 election (a seat to the

Imperial Legislature in Delhi), due to it not backing him sufficiently. He left

Congress, in a huff. Another wounded ego was

that of Thiyagaraya Chettiar, who was denied a seat on the podium at a temple

festival, as a lower caste, even though he had been the biggest donor for the celebration.

The common grouse of both Nair and Chettiar was thus the Brahmin posturing at

the prime position in the caste ladder, something they would not tolerate.

Everything they did later, was to bring down the pillars of this caste hierarchy.

Notwithstanding all that, Nair also cared about the common man and the Swadeshi

movement was something he stood for, and in 1905, he referred to the exemplary

decision by the Irish house of commons to use locally made apparel and furniture.

Even though Nair was

not anti-brahmin and did admire some of their educated and good qualities, he maintained

that the non-Brahmin who could be as good, or better, was unnecessarily kept

down. His opinion put eloquently was – The brahmins toiled not, neither did

they spin – The sweating slaves supplied them with everything, and they, in

turn, cultivated spirituality. Soon Nair was frequenting stages with his popular

and strident anti-Brahmin tirade which many thousands attended, which was the

start of the Dravidian movement of 1916.

Nair’s tenure in the Justice party

In Nov 1916, some 30 odd leaders, including T M Nair and P

Tyagaraja Chettiar, met at the Victoria Public Hall in Madras to form a joint-stock

company, the South Indian People's Association, to publish newspapers in

English, Telegu, and Tamil to express non-Brahman grievances. Within a month, they

issued the 'Non- Brahmin Manifesto' and announced the formation of the South

India Liberal Federation with explicit ideological and political lines. That

was the start of the Justice Party. Nair never attacked religion but always focused

on representation. Heavily funded, the party had no difficulty taking off. The party

ran an English newspaper called The Justice, with Nair editing it, until his

death in 1919. At that time many opined that the Justice Party was supported by

Montague to get support for his reforms, and people had a feeling that the

Justice party was too pro-British, augmented by the fact that Justice condoned

Gen Dyer for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and also opposed non-cooperation. The

Justice Party also supported the relative continuance of British rule in return

for a proportionate reservation of seats in the Madras Legislative Council. Even

though they did a lot of good for the local non-Brahmin populace, they were often

accused to be British puppets, and in nonconformance with the national

movements led by Congress.

Montford reforms

Dr. Nair was the only

non-Brahman leader who made a strong impression on Montagu. Montagu concluded

that Dr. Nair was “most eloquent, rather impressive, and a vigorous

personality, but he has obviously got a bee in his bonnet, because he

explained that the Home Rule movement was financed by German money, nevertheless

pointing out that he was very fierce on communal representation. Montford

reforms – a usage coined by Nair (Montague Chelmsford) covering the introduction

of self-governing institutions, gradually in British India, was not very

popular upon release and felt to be insignificant. Nair did not agree to its

meager non-brahmin representation and eventually got a chance to go and argue

his case in Britain, in 1918. His

connections with Britain and his ability to speak forcibly were of critical

importance in the demand for communal representation from Parliament, and the

reason for the party’s choice as their spokesman.

A furor erupted when he was issued a passport - Tilak was not issued a passport, but Nair was,

resulting in rumors that it was because the Justice party supported the

British. A new report said – The Government had granted a passport to, of all persons - Dr. T. M. Nair, the

anti home ruler, the political renegade, on the allegation that he (the sturdy,

stalwart, stupendous Madras doctor) had become such a physical wreck - as to

require attention in Britain. The

British administration clarified that they granted it only due to health

reasons. In reality, he was in poor health and suffering badly as a result of

advanced diabetes.

Final visit to Britain, death

Nair’s trip to London in 1918

was a success, he spoke well and his arguments were listened to carefully.

Upon his return to Madras, he was convinced that

modified reforms would pass. But the

situation did not change and the representation demands did not pan out. Things went from bad to worse and Nair was

deputed again to go to London and argue the case. Nair quite ill by now knew

that his return to India from that trip was no longer certain. On reaching

London, preparations for the speech started, Nair finalized the draft and

provided key contact details to his team, as his health was failing rapidly. Eventually, he passed away in his sleep, on

July 18th, 1919, and was cremated at Golden Green. KPS Menon

studying at Oxford attended. Many obituaries were written, and his passing left

the Justice party rudderless, for a time.

It was during the 1918 trip that KM Panikkar, then studying

at Oxford, met him. He records this in his autobiography - Dr T. M. Nair was

a very different type. There never was a manlier Malayali. A leonine face, a

long curving moustache, massive chest, a somewhat portly figure and powerful

arms made up his impressive physical presence. His intellect and powers of

expression were equally uncommon. One had only to talk to him for a couple of

minutes to fall under his spell. In the most eminent company. he achieved

effortless primacy. I have never seen an Indian to equal him as a

conversationalist. Although T. M. Nair achieved fame as a skilled physician,

his astonishing intellect could master any subject with equal ease. As leader

of the Madras Corporation, he was ready to discuss engineering with engineer

and law with lawyers. In civic administration, he had no peer in South India.

As an editor and orator, he was matchless. Above all, he was eminently

sociable. He was a connoisseur of food and drink, with unerring taste for wine,

tobacco and good cuisine. A bon vivant, Nair was always open-handed with his

money. In spite of this cosmopolitanism, Dr Nair never ceased to be a Malayali

and I have often heard him quote Nambiar and Ezhuthachan in conversation.

People remember him today as the founder and leader of the non-Brahmin

movement. Although the force of the movement has now waned, T. M. Nair will not

be forgotten by Madras. Nair had come to London to lobby against the

Montague-Chelmsford reforms. Although I had no sympathy for his views, I was

eager to meet such an eminent personality. I was introduced to him by Sir Frank

Brown, an assistant editor of The Times. We were close friends for about three

or four months and I used to meet Dr Nair almost daily in the period just

before my return to India. He returned to India a month after I did, but ironically,

we were not able to meet in India.

Post Nair years – Justice Party

After his death, the party declined to cooperate with the Southborough

committee which had been appointed to draw up the franchise framework for the

proposed reforms, due to Brahmin presence in the committee. After negotiations,

a compromise ("Meston's Award") was reached in 1920. 28 of the 63

general seats in plural member constituencies were eventually reserved for

non-Brahmins.

The Government of India Act 1919 implemented the

Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, instituting a Diarchy in Madras Presidency. The diarchal period extended from 1920 to

1937, encompassing five elections. Justice party remained in power for 13 of 17

years, save an interlude 1926–30. After Justice won the election and got into

power, they initiated several egalitarian moves such as the upliftment of women

and the marginalized, access to water (for the lower castes) from public ponds,

women’s suffrage, abolishment of the Devadasi system, regulation of college admissions,

etc.

Nevertheless, many of Dr. Nair’s ideals were forgotten after

his death. Social injustice perhaps dropped lower in the list of concerns, and

party infighting ensued. Neither Brahmins nor Muslims supported Justice and

membership declined when some lower castes also left the party in a huff. Eventually,

the party was voted out of power and remained in the political wilderness until the

arrival of Periyar EV Ramasamy in 1938 who transformed it into the Dravidar

Kazhagam in 1944.

Though there are roads, medals, and schools, still around,

instituted in Nair’s honor, nobody quite connects those to the persona who once

was a byword in Madras. In his heydays, any luminary visiting Madras made it a

point to call on him and a notable mention is that of the great painter Ravi

Varma and his uncle, who called on him often when they visited Madras in 1902,

recording the event. Many papers and booklets authored by him are testament to

his brilliant mind, medical, social or political.

Kerala forgot Dr. Nair a long time ago and only a few in

Palghat still connect to the name. The Tharavath home is a Kalyana mandapam

these days. But I think this essay may go on to remind some that a great man

once lived a short life, fought for the repressed and for their equality, always

standing up and talking to the British, on equal terms.

Politics and Social Conflict in South India - By Eugene F. Irschick

The Justice party – Dr P Rajaram

Parliamentary Papers, Volume 74

The non-Brahmin movement and Dr. T.M. Nair – T.P Sankarankutty Nair

Dictionary of national biography vol.3, TM Nair – TK Ravindran

An Autobiography - KM Panikkar

On a lighter vein

AV Menon contributing to a Khushwant Singh’s joke book has

this to add - Dr. T. M. Nair, a well-known politician of Madras of the early

nineties, while in London used to frequent a particular pub in the East End.

His usual drink was a cocktail of vermouth and gin, the code word for which

between, his regular waiter and himself was ‘virgin’. Once in the absence of

the regular waiter, the one substituting for him came to take Dr. Nair's

orders. "The usual virgin", Dr. Nair said. After a minute or two, the

waiter came back and whispered into the ear of his client, "One cannot be

found in London at present, Sir."