SE Asia’s roving newshound

News used to be reported from the source with engaging text by

journalists, and the challenges they faced and the risks they took are fodder

for so many thrilling tales. These days, however, distant back offices help

complete news bits with little personal involvement, and pretty soon we will

see AI engines churn them out instead. Perhaps it is time to take you back 80

years and get to know a journalist who lived through two world wars and delivered

news articles from many locations under duress. This interesting gent who evoked

envy and grudging admiration among his peers and juniors, and delivered many a

scoop in the 40s and 50s, was none other than Madhavan Sivaram, the intrepid

journalist and author of many seminal works from his time.

Sivaram was born in Nov 1907 in Travancore’s Kuttanad region

(South of Alleppey), hailing from the Konnavath tharavad. It would be

incredibly difficult for a lay reader to fathom how a boy who never completed

college, who worked briefly as a schoolteacher and married young, decided one

fine day to simply leave his home and wife Janamma, to chase his dreams and

make something of himself in 1929. Fortuitously, or not, after hours of

self-study, he had mastered English, and this was to stand in good stead as he

prepared to seek a job in the busy metropolis.

Sivaram as we can understand, landed up at the doors of the

Associated Press of India (API) offices, in Bombay. Life in Bombay was

certainly not fun, post WW 1, as press censorship was rife, newsprint was

scarce, working conditions were tough, and the salary was meager. Sivarama

Pillay had by then become M Sivaram. When a more affluent life beckoned in

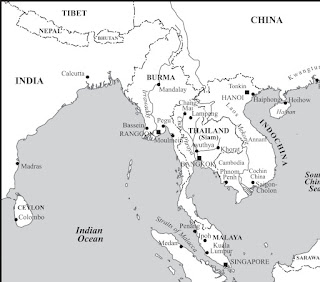

Rangoon, much like Dubai and the Gulf these days, Sivaram boarded a ship to

Burma, and armed with the short experience at API, took up a job with a Rangoon

newspaper as a proofreader. After a short stint in Rangoon, he moved on to take

up an Asst Editor’s post in the fledgling newspaper “Nation” in Bangkok. Pretty

soon, his skills became apparent to the news fraternity, and he snagged an even

better offer as chief editor at the ‘Bangkok Chronicle’.

Bangkok became his home for the next 10 years. His wife

Janamma joined him, and his three children were born there. Sivaram’s newspaper

career thrived and as Siam was growing from a small kingdom to a lively republic,

Sivaram formed a great relationship with the King and many other luminaries in

Bangkok. His first book; The New Siam in the Making - A Survey of the Political

Transition in Siam, 1932-1936’ was written during this period. A close friend

of the King of Thailand and the Prime Minister Field Marshal — Song-Khram, he was

the recipient of the Thai ‘Medal for Home Defense’ (equivalent to the Iron Cross

– which saved him from being shot at least twice), and was highly respected in

Siam. It is said that the king awarded him together with the medal, a grant of

40 acres of land in central Bangkok, which the journalist politely refused. A

second work followed – ‘Mekong Clash and Far East Crisis: A Survey of the

Thailand-Indochina Conflict and the Japanese Mediation and Their General

Repercussions on the Far Eastern Situation 1941’. Those happy days in Siam are

narrated in his book - Road to Delhi. A profile entry mentions that he also did

some stints in Singapore & Hong Kong (Hong Kong Courier).

In India, the freedom struggle was heating up, and but naturally, expatriates in SE Asia took notice and formed associations and groups, in solidarity. Speeches by Gandhi, Nehru, and other INC leaders were eagerly followed, and local procession meetings, as well as protest gatherings, increased. Sleepy estates with large numbers of Tamil and Telugu laborers joined processions supporting the freedom movement. We had previously studied the IIL activities, formation, and development while discussing TP Kumaran Nair, N Raghavan, and AM Nair. Sivaram too was drawn into the Indian Independence League activities which had originally been concentrated to just Singapore.

To recap the IIL moves – Rash Behari Bose, who had fled

India to seek refuge in Japan, had cemented his relationship with the Japanese

and established himself in Tokyo, forming an Indian association in 1926. In

1937, the IIL Japan branch had been set up. The Indian Independence League IIL was

a political organization, formed to fight for Indian Independence, but also

carrying out local social service. Soon the organization boasted branches in

every city which had a sizeable Indian community. Sivaram got involved in

Bangkok’s IIL activities, as well. Another character whom we have talked about

previously and central to the INA organization, namely SA Iyer had also arrived

in Bangkok and was working as the Reuters correspondent for SE Asia.

Meanwhile in 1939, war had spread in Europe. Japan was at

the war front too but fighting the Koreans and the Chinese. AM Nair, Bose’s

deputy in Japan, was the ‘Ronin in Manchuria’, a story which I had recounted

some years ago. Indians fighting for freedom now saw a new opportunity to press

their case. While Germany was annihilating opposition on the European front,

the Japanese, convinced by Rash Behari Bose and AM Nair, decided to support the

Indians, albeit to ease their own way into the Indian border through Burma. The

Indians in SE Asia had a problem though, the INC supported China, which was at

war with Japan, so all influential Indians were anti-Japan. The astute

journalist sensed the looming war clouds and potential war movements in SE

Asia, left for India on a cargo ship going to Nagapattinam in Nov 1941, to drop

his wife and family at Travancore, and quickly returned to Bangkok. For the

next 5 years, Sivaram was to operate alone, flitting between Malaya, Singapore,

Rangoon and Bangkok.

In Dec 1941, Japan attacked America at Pearl Harbor and

joined the Axis powers. The war in Europe had become a world war. The Japanese

war machine defeated the British at Singapore, sped through Malaya, and stopped

at Burma to recoup and restock. The Indian frontier at Assam was next, and while

they waited at Rangoon, the defeated British Indian army soldiers were

contacted by the IIL leaders and reconstitute themselves for Indian liberation,

marching side by side with the Japanese. Indians in SE Asia rallied to the

calls of the IIL and saw in the Japanese a friendly ally. The Thailand government

concluded an alliance with Japan after a 5-hour resistance and Sivaram decided

to stay and brave it out in Bangkok, concentrating on IIL’s activities.

The formal incorporation of the IIL was announced in Bangkok

in June 1942 and as you can imagine, AM Nair and Rash Behari Bose leading those

efforts, were supported by Sivaram and Iyer who were residents there. Nair

convinced Bose that the IIL management should include Sivaram. As Nair explains

- Rash Behari at once agreed and decided to nominate him as the League’s

spokesman and publicity officer. Sivaram, captivated by Rash Behari’s charming

personality and persuasive manner, discarded all other activity, and joined the

League heart and soul, to handle its publicity portfolio. With the help

of M. Sivaram and the support of S.A. Iyer, we organized a good publicity

campaign in Bangkok, both in the newspaper media and over the radio.

Sivaram wanted Iyer (in the lurch since Reuters London had

no instructions for him) to join him but was not able to convince him initially,

as he considered working for the Japanese quite dangerous. Aiyer adds- Sivaram

coaxed, cajoled, and literally dragged me to Rash Behari much against my will.

Not even a hundred Sivarams could have dragged me away from Rash Behari after

that first meeting. Rash Behari had a specially warm corner in his heart for

Sivaram because, unlike me, Sivaram threw himself heart and soul into the

movement from the moment Rash Behari reached Bangkok. And the old man being very

human first and last, responded to this gallant gesture of Sivaram with a love

and affection which would bring out tears even in the eyes of brutes. And

Sivaram, for his part, today carries the sacred memory of his Sensai (teacher) in

the warmest corner of his heart, and sustains himself with it night and day,

wherever he may be.

Rash Behari was however a very ill man, suffering from TB, and

so the freshly constituted INA required new blood. The charismatic Subhas Bose who

arrived from Japan after Berlin, was introduced to the IIL unit in Singapore,

arriving there in 1943. Bose, Nair, Iyer, and others such as KP Keshava Menon, N

Raghavan, etc. teamed up to create the new INA, with Subhas Bose in command. Needless

to state that the situation became a bit turbulent as Subhas Bose who tended to

be quite authoritative at times, sidelined the popular KP Kesava Menon who

muttered about Bose’s fascist dictatorial stance, and had him jailed. It is all

a long story and suffice to mention that the overriding desire to obtain Indian

freedom became foremost in everybody’s mind. They maintained strict discipline

and secrecy – Iyer mentions - My friend and colleague, Sivaram, also did not

send even a single message (home to family in India), although we two,

discharged, among others, the duties of the Director and Deputy Director

respectively of the Singapore Radio Station of the Azad Hind Government.

|

| Sivaram with Subhas Bose |

But eventually, a working relationship was established, egos

were mostly forgotten, and the publicity group moved to Burma. On the

professional front, even though working for the IIL and the INA, Sivaram was

working for Reuters as well as their regional manager and chief correspondent.

He is one of the rare writers who recalled the tragic recruitment and virtual

enslavement of the many thousand Tamils who were put to work on the Thai Burma

death railway and of the thousands who perished.

AM Nair continues - A little earlier, around October

1943, Sivaram and a small publicity staff under him had proceeded to Rangoon

under Subhas’ instruction, to reorganize the propaganda work there. Initially,

Lt. Colonel Kitabe, the head of the Hikari Kikan in Burma, was unhelpful, but

Sivaram soon won him over with his tact and managed to set up an effective

publicity organization for conducting programs from Radio Rangoon. It was a

risky assignment since the whole area was exposed to British bombing. Sivaram’s

house was hit during one of the raids. It was a miracle that he survived. The

Azad Hind, selling at 5 cents a copy and boasting English and Tamil editions,

was a leading example of Sivaram’s work. It was structured along the lines of the

Singapore newspaper. He had as many as 300 young men training under him for

this work.

In 1944, Bose, who believed that Gandhi, Jinnah, and Nehru

would never fight against the British, moved to Rangoon and spearheaded the ill-fated

Arakan campaign which stuttered, stalled, and eventually collapsed at Imphal.

After the Imphal debacle, Sivaram, who had been unhappy in Rangoon, though

still holding Bose in high regard, resigned from the INA, and returned to

Singapore to continue with INA publicity work. However, were not going well

there either, and it was decided to send Nair and Sivaram back to Japan. Sivaram

was to go there to study Japanese diplomatic practices and procedures, which

could be useful in the new India under Bose. Together with his ten publicity

assistants, Sivaram joined Nair in Tokyo during the second week of Oct 1944.

Living in Tokyo was incredibly dangerous, Tokyo and other

cities in Japan were under heavy American bombardment, and the situation was

worsening every day. Sivaram and Nair did whatever was possible, to keep up the

broadcasts from Radio Tokyo, covering many events, but they knew that the end

was near. As the situation became dire, Nair arranged for Sivaram’s departure

back to Singapore with a military escort, and the latter managed to get out,

just before Rash Behari passed away in Jan 1945 (Another source however

mentions that Sivaram went to South Siam). Aiyer corroborates - M. Sivaram,

the spokesman of the Provisional Government of Free India, took them to Tokyo,

put them in the way (running the radio station even after others had

stopped) and returned to Singapore after a few months.

The British were moving in to retake Burma and as the

Japanese situation became untenable, the Azad Hind government withdrew from

Rangoon to Singapore, along with the remnants of the 1st Division and the Rani

of Jhansi Regiment. Bose planned to go to the Soviet Union via Manchuria and according

to reports, died from third-degree burns received when his overloaded plane

crashed in Japanese Taiwan on August 18, 1945.

Whatever happened to Ayer and Sivaram? Ayer was taken to

Delhi to give evidence and became a key defense witness in the first INA trial.

Janamma was informed by Ayer that Sivaram was presumed dead, but refused to believe

the news. That was the first announcement of Sivaram’s death, which was soon voided

by Aiyer who later confirmed that he was alive and healthy. Sivaram got back to

Mavelikkara, after selling his typewriter for passage, and it is understood

that he was interrogated by the British later.

Sivaram went back to Bangkok and continued as a roving

correspondent for PTI and Reuters as their foreign editor. Alexander, his old

Travancore friend at Bangkok, was still around and running his brass, silver,

and jewelry business, the popular Alex & Co, at Oriental Ave.

Sivaram recorded the biggest scoop in his journalism career

reporting the gunning down of Burma’s first Prime Minister Aung Sang with his ministers.

Sivaram recounts (Brave New

Burma – Democratic world 1981) – I happened to be in Rangoon those days,

as a correspondent for Reuters. By some queer luck, I was standing at the

telegraph office, opposite the secretariat when the gunmen drove in, in two

Jeeps, shooting right and left. I ran after the gunmen who drove out in less

than two minutes, shooting in all directions. I peeped into the cabinet room,

which was left open by the gunmen, to find Aung San and his colleagues in a pool

of blood, and the walls of the room plastered with bullets. I ran back to the

telegraph office and managed to send a brief urgent cable, which got out before

the Government clamped down a twenty-four-hour censorship of all news from Burma.

That little story, of the grim tragedy in Rangoon, was one of the three major

world scoops of 1947. Later U Saw was tried and hanged for the mass murder of

ministers.

Oct 1950 – The Chinese accession of Tibet, and the statement

from Chinese officials that the action was carried out to forestall an

Anglo-American plot against China, with Indian support, was reported by Sivaram.

After these dispatches, Sivaram was treated with great

suspicion by the Chinese, since PTI was now being considered imperialist due to

the Reuters connection. Sivaram decided to leave China and managed to do so

eventually. He continued his Reuters reporting from Hong Kong and his expose of

Chinese plans & preparations to enter the Korean War, was suppressed by the

Indian government. His report was not appreciated by the Indian foreign

ministry and his PTI report was blocked (It started thus – “Communist China has

completed preparations to throw half a million crack troops into the battle for

Korea ' even at the risk of a major war”), it is believed at the behest of

Nehru and NG Ayyangar (Nehru later fumed in parliament that Sivaram’s reports

were indiscreet, exaggerated, and unhelpful), since India supported China in

those days. Reuters abided by this suppression, and the only reporting was in

Australian newspapers. As it transpired, Sivaram's report was perhaps the most

brilliant one sent by any correspondent during the entire Korean War,

forecasting with accuracy, the political and military developments.

Korean War 1950-53 – I had written about the Korean War and

the role of VKKM, Thimayya, Kaul, etc., but did not cover Sivaram who was also

there as the PTI correspondent. After failed attempts at negotiations on

unification, the North Korean military (KPA) crossed the border and drove into

South Korea on 25 June 1950. Later in October 1950, Mao’s PRC committed

approximately 260,000 troops to combat. Chinese troops attacked and surprised

the UN forces, inflicting heavy losses while driving them down the peninsula in

disarray. The Chinese continued with more brutal offensives between October

1950 and April 1951 but failed to impose a communist government on a unified

Korea.

Sivaram’s report - Inside Soviet China, 1951, and his

articles Behind the silken curtain - China people's Democracy is a Fraud,

dated May 1951, Mao-ism - Red China's New National Culture in the Malaya

Tribune, 18 January 1951 are quite interesting reads. Later, parts of his China

diary were serialized in the ‘Democratic World’ journal. Considered a SE Asian

expert, he could speak Burmese, Malay, Thai, Indonesian, and a smattering of

Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, and Korean. Of course, you should add English,

Tamil, Malayalam, and Hindustani to the polyglots list. Let’s now pause and

check what happened at Korea.

Sivaram holds the honor of being the first non-communist

correspondent to cover the war in Korea from both sides of the parallel. Interestingly

it was at this juncture that Col MK Unni Nayar of Palghat was killed in a mine

accident, together with two other journalists. Usually, Unni was accompanied by

his friend and countryman Sivaram, but Sivaram had flown to Japan the previous

day for R&R, and the press, assuming that Sivaram was one of the

journalists killed, reported his death, wrongly, for a second time.

The next scoop was from Cairo – On 23 July 1952 at about 1

am, Free Officers launched the revolution with a coup d'état to depose Farouk. It

was Sivaram who reported exclusively from Cairo on the ouster of Prince Faroukh

of Egypt in 1952 and the army takeover by Gen Naguib.

Journalist Kamath continues the story, in his memoir -

Sivaram had fallen foul of Jawaharlal Nehru in his coverage of the Korean War

for the Press Trust of India and had retired from PTI, when we took him.

And that was how Sivaram ended up joining the Free Press Journal after Sadanand

passed away. SA Aiyer (who was at that time the director of Information in the

Bombay govt) had recommended him and he was appointed as FPJ’s Acting Editor, with

AB Nair as his mentor. However, he did

not get along well there, as an anti-communist, editing a left-leaning newspaper. Sarat Chandran Nair and others have left

accounts of Sivaram’s days at FPJ and how Janamma used to treat all his

Malayali friends with home-cooked food etc. Interestingly, Kamat remarks that

he had edited Aiyer’s ‘Unto him my witness’, but Aiyer states in the book that

Sivaram edited his book in 1951.

He moved on to the AIR in 1953 as its Director of News

service, though after a couple of years, he was back to journalism as the Editor

of the India news service (He did give an AIR talk on Rash Behari in Jan 1959).

Five years later he went back to SE Asia – as the editor-in-chief of Malayan

Times in 1962 but returned to India after legal issues with the paper’s owner

who owed him $16,000 in back wages.

He then took up roles at the Indian Express, first as a Consultant

at the International press institute in 1962, then in 1964 as Indian Express Bureau

chief, and again as Consultant International press institute in 1965 (It was

during this period that he wrote about Vietnam and its people. The Vietnam war,

why? Which was published in 1966). His last assignment was with the SE Asia

Press Institute on behalf of the IPI Zurich at KL and Jakarta – 1966-67, this

was when the ‘Malaysia’ book was penned. As an IPI consultant, he took classes

for budding journalists in Korea & Singapore – on how to write a lead and

edit a copy, where to look for a story, what investigative reporting was all

about, the basic principles of good writing, clean makeup and creating a smart

headline. I wish I had a chance to attend something like that!! It proved very

popular, and Sivaram had to split the eager participants into multiple groups.

One of his last official acts was to interview Swami

Chinmayanada (who had once been a journalist as well, for the National Herald!)

in April 1968, as well as deliver a talk on the Azad Hind in Oct 1968, for the

AIR. In addition to reporting for Reuters London, he did a stint at the UN in New

York and contributed to The Sunday Times and The Guardian. He also gave

evidence to the Khosla Commission in the 70s.

Fatigue must have been gnawing at his bones, he finally retired

and moved to his new home ‘Newshouse’ at Kowdiar in Trivandrum, nevertheless,

continuing to file some reports for Nava Bharat Times. He then helped set up

the Trivandrum press club and became its president, and started the Institute

of Journalism in 1968, training young journalists and regaling them with many of

his experiences.

Sivaram passed away after a heart attack on Nov 20th,

1972. The pen that drafted many a thousand words would write no more and the

typewriter that delivered many a finished article, was to remain silent – its

clickety-clack silenced forever.

Today he is remembered through the M Sivaram Award for News

Stories and Features.

References

Road to Delhi – M Sivaram

Mahacharithamala Vol 65 - R

Radhakrishnan, Suresh Vellimangalam

Unto him a Witness - SA Aiyer

An Indian Freedom Fighter in

Japan: Memoirs of A.M. Nair

The Dismantling of India – in 35

portraits – TJS George

Ottayan, Ghoshayatra – TJS George

Democratic word – Sivaram’s diary extracts

Photos – Courtesy

Ananda Sivaram, Mahacharithamala

Many thanks to Anitha Devi Pillai at Singapore, for helping

me establish contact with Ananda Sivaram, M Sivaram’s eldest son, and my

gratitude to Ananda for talking to me and providing me with inputs, news

clippings, and magazine extracts.

Related articles – Maddy’s Ramblings