A Greek sailor’s trip

to Malabar circa 355-363 AD

Deeply buried in the many layers of ancient history

connected to the Malabar West Coast is the story of the Theban lawyer, one that

has not been studied in detail as yet by Indian historians. It is an

interesting story, but one which has so many contradictions within it that it

is quite difficult to dredge out the bits of fact from a good amount of

fiction. The problems arise when orally told tales are retold many times over

and finally committed to text. Animals become dragons, men become ogres, women

become mermaids and unimaginable acts are attributed to barbarian civilizations

living far away. To pick up fragments of useful facts from such texts are, as

one can imagine, quite tedious. Nevertheless, let us take a look at this adventurous

tale which dates back to the beginnings of the Anno Domini era, but for that we

have to start with a location in Roman Egypt, named Thebes.

Thebes known to the ancient Egyptians as Waset, was an

ancient Egyptian city located east of the Nile about 400 miles south of Cairo,

lying within the present day Egyptian city of Luxor on both the banks of the

Nile, where the temples of Karnak and Luxor stand. The Assyrians were the first

to pillage and plunder the wealthy city of Thebes around 667BC. The Greeks

followed with Alexander in the lead but after a relatively peaceful period,

successive revolts lay its population open to invasion by Rome. During the

Roman occupation, Thebes became part of the Roman province of Thebais. The legend

of the Theban legion, some 6000 Romans who converted enmasse to Christianity, if

you recall, figures prominently in history. Following this there is indication

of the presence of Diocletian’s Roman army in Luxor. Rome’s governance of Egypt

was orderly, based on prefects, justice administrators, revenue officers and so

on. The metropolis and their local officials shared in the burden of provincial

government, especially as related to the transportation of supplies and

collection of revenue. And importantly, the main produce of Egypt, that of

prime importance to Rome was grain cultivation. More than all that, the Red Sea

ports close by were the ones who conducted all the trade with erstwhile India,

mainly the trade emporia on her western coast. It is also apparent that the

author was not from Greek Thebes for it had lost all importance by then.

Roman legal practices were laborious and the classic law

practices demanding and exact. One not keen on such a trade is prone to getting

bored with that kind of thing and would but naturally not be able to scale its

career ladder. Our hero was one such person, and he was getting tired of being

a lawyer and as is evident, he was from the Scholasticus breed, a special class

of trained civil servant and lawyers, created after the Emperor Diocletian’s

time. Maybe he heard tales of wonder from the world yonder from sailors

disembarking after perilous voyages to Malabar, braving the Hippalus monsoon

winds. He heard stories of immense

wealth, practices of a land with strange people where spices were grown.

Perhaps his imagination was stoked just enough, for he soon decided to forsake

his tedious desk job and plan a trip to the land of spices.

We cannot yet be sure that his destination was a port in

Malabar. That Rome conducted its trade mainly with Muziris south of Malabar is

clear, we have discussed this at length, we discussed the famous Muziris Papyri

some years ago. We also noted that winds did change course for long periods now

and then and thus a number of Arabian sea ports appeared on India’s West Coast,

each going on to become a favorite of a type of trader, all of which we

discussed in a previous paper (Hubs of medieval trade) I had written.

The Greeks described Muziris in Periplus thus - Then come

Naura and Tyndis, the first markets of Damirica (Limyrike), and then Muziris and

Nelcynda, which are now of leading importance. Tyndis is of the Kingdom of

Cerobothra; it is a village in plain sight by the sea. Muziris, of the same

Kingdom, abounds in ships sent there with cargoes from Arabia, and by the

Greeks; it is located on a river, distant from Tyndis by river and sea five

hundred stadia, and up the river from the shore twenty stadia. Trade continued

to peak with the Romans who followed Greeks though it declined from the mid-3rd

century during a crisis period in the Roman Empire, but only to recover in the

4th century.

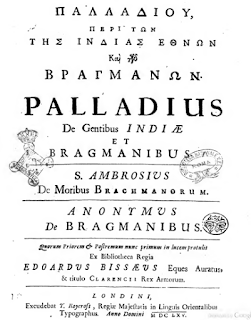

It was at this juncture that our man Thebes Scholasticus decided

to take a trip to India. But before we get to his story let us see how his

account comes to light. It appears that he narrated his story to an Egyptian

Greek scribe named Palladius who added parts of it to his account of the

Brahmins of India. I will not get into the details of why Palladius wrote about

Brahmins, needless to say that their (i.e. the ancient chaste Brahmins) lives

and methods were a source of immense curiosity since Alexander met some and

took one home with him (see my article on Calanus).

What Palladius did was collect a lot of matter from here and

there, which included narration from our lawyer and made a booklet titled

‘Palladius on the races of India and the Brahmans’. This booklet if perused in

all seriousness would be an ‘avial’ of varying tales (mishmash of various

vegetables cooked with coconut – a Kerala delicacy) and second hand information

available from disembarking sailors and traders.

Three scholars took to studying the travails of our Theban

lawyer in right earnest, the first being the English scholar Duncan Derrett.

The second was the French historian Jehan Desanges and the third who studied

the above papers and came up with a more detailed analysis was the eminent Sri

Lankan Academic, the late Prof DPM Weerakkody. As for me, I am just the lucky

person who laid hands on these carefully worked papers and am presently trying

to make some sense of all that with a Malabar point of view.

That said, Derrett documenting his findings in 1962, lays

his theory on why this Theban lawyers voyage could be dated to the 4th

century, and goes on to narrow the travel dates down to 355-363AD. He then

establishes that since there is a mention of the land where pepper grows in the

text, the destination was Malabar. But there were a number of contradictions

too, and these aspects will be looked into a bit later (Note: The main

translation of the Greek Palladius text used here, is the one provided by

Berghoff).

To get to Malabar in his days, it appears that he had to go

to a Red Sea port called Adulis. Covering parts of what is now northern

Ethiopia and southern and eastern Eritrea, Aksum was deeply involved in the

trade network between India and the Mediterranean (Rome, later Byzantium),

exporting ivory, tortoise shell, gold and emeralds, and importing silk and

spices. Starting around 100 BC a route from Egypt to India was established,

making use of the Red Sea and using monsoon winds to cross the Arabian Sea

directly to southern India. The Kingdom of Aksum was ideally located to take

advantage of the new trading situation. Adulis soon became the main port for

the export of local goods, such as ivory, incense, gold, slaves, and exotic

animals. From Adulis, a caravan route to Egypt was established which bypassed

the Nile corridor entirely and allowed for goods to reach North Egypt and Alexandria

for further movement to consumer centers in Europe. Adulis incidentally, lies 40

miles to the south of the modern day port city of Massawa and near the village

of Foro, a sub-zone of Zula in Eritrea. It lies south of Bernice which was also

famous for its Indian connections.

And so our man decided to go to Malabar and went to Adulis

where there existed a trading Indian community which had its own chieftain. He

learned a bit of their language and next decided to sail on to Taprobane or

Ceylon. One could of course wonder why he chose Ceylon, though it was well

known, it was not yet on the trading map of that era, perhaps he thought he

could make a killing, become famous and rich as a pioneer with Ceylon trade.

That decision it appears and we shall soon see, was to become a reason for his

downfall.

Anyway he found passage in an Indian vessel. An extract from

a translation of his original account in Greek, tells us the following. In the company of a "Presbyter" he

sailed along and touched in first at Adulis (on the Abyssinian coast), and then

at Axume, "where there was even a minor kinglet of the Indians in

residence there. There he spent some time and gained a deep acquaintance with

them and he wanted to go to the island of Taprobane also where the so-called

Macrobioi live.

Let’s stop here for a while since the Theban goes on to

explain that the Macrobioi have a long life span of upto 150 years. Was he

planning on establishing contact with the Macrobioi to learn their longevity

secrets? I can only assume he did not, as a typical lawyer, believe that longevity

was due to the oft mentioned reason of the islands salubrious climate and gods

will.

The account goes on to mention the 1,000 odd magnetic

islands enroute which prevents boats with iron nails from passing and allows

only boats using wooden pegs or nails for fastening. He details the island of

Taprobane which he has heard about, which had coconut trees, arecanut trees, that

they lived on rice, fruit and milk, and had goats. They wear skins round their

middles. The island has no pigs and has

five large rivers. All stuff he had heard and most seem right from what we can

imagine. But how come he never reached there? Let us continue to pick the

threads of the Theban tale for here is where hell breaks loose and the

descriptions falls apart…

Continuing on - He

found some Indians going by ship from Axume for the purpose of trade, and he

tried to get further east. He reached the neighborhood of the people called

"Bisadae", the pepper gatherers. That people is very small and weak, they

live in caves and the rock and are capable of making their way on precipices

because of their acquaintance with the locality, and that is how they gather

pepper from the bushes, for the bushes are also stunted as that scholasticus

said. The Bisadaes too are stunted little fellows with big hands, unshaven and

lank-haired. The rest of the Ethiopians and Indians are black, upstanding

fellows and bristly-haired.

Now let’s stop and think. He has sailed with the Indians to

reach a pepper gathering locale where tribals deliver the pepper grown in the

highlands. Derrett believes it could have been Porkkad or Baccare (Vaikkarai)

but the latter could be ruled out since we are talking about pepper which was

cultivated only on the west of the Western Ghats. It could also have been any

other port but not Muziris, a train of reasoning which we will soon come to

terms with.

We see that the Theban lawyer is arrested as soon as he

lands. Perhaps the companions of the lawyer explained to the local chieftain

that this fellow was planning to move on to Ceylon and had other ulterior

motives such as establishing a parallel trading outpost, perhaps it was to

usurp their secret to longevity. Anyway he is arrested.

Then, he said, “I was

arrested by the local ruler and was tried for daring to enter their country. They

did not accept my defense since they did not know the language of our country,

nor did I understand the charges they brought against me, for I did not know

their language either, but simply by the twisting of the eyes we communicated with

each other in recognizable gestures. I came to recognize their accusing remarks

from the bloodshot color of their eyes and the savage grinding of their teeth,

and guessed the meaning of what they said from their movements. On the other

hand, from my trembling and anguish and the paleness of my face, they clearly

realized my pitiable state of mind through my physical trepidation."

So I was arrested and

was a slave among them for six years, handed over to work in the bake-house.

The amount spent by their king was one modius of corn for his whole palace, and

I don’t know where it came from. And so, in these six years I was able to

interpret a great deal from their language and hence I have got to know the

neighboring tribes besides.

I was released from

there in the following way: Another king made war on the one who kept me

captive, and accused him before the great king who resides in the island of Taprobane,

of taking prisoner an important Roman and keeping him in the basest servitude.

The king sent a judge, and upon learning the truth of the matter, ordered him

to be flayed alive, for doing injury to a Roman, for they respect and fear the

Roman Empire very much, thinking that it could even invade their country

because of its supreme courage and inventive skill.

With this the Theban bows out from the Palladius text,

leaving behind intriguing questions. Where did the ship take the Theban to? Who

are the stunted tribal people? Would a Roman be put on kitchen duty for six

years, even after he is said to have learnt the local language? Who is the

great king of Taprobane and what relations did Ceylon kings have with Malabar

or other nearby states? Who are the Besadae? Why is corn mentioned as a meal

component in a Malabar palace? Is public flaying a method of punishment in

Malabar and thereabouts? What was the local norm of justice considering the

Theban was arrested straightaway? Why were the locals or for that matter the

great king at Taprobane fearful of the Romans? Why did the Theban not sail on

to Taprobane after release? How did he return to Thebes? Was the location on

the Eastern side perhaps a place like Puhar where Romans were often destined? Or

further up the Bay of Bengal? Let’s now get to the answers.

While Desanges believes the location where the Theban lawyer

ended up was close to Assam, mainly due to the mention of the location Bisadae

(and the Mekong valley dwarfs), it is more probable that he was captured by one

of the hill or forest tribes of ancient Malabar and imprisoned by them. Perhaps

he strayed too deep inland to discover the secrets of pepper growing and was

picked up by this tribe. Larger principalities had more organized legal

structures, were more hospitable to foreigners and punishment such as flaying

of the king himself is unlikely. The use of corn is very strange, and there is

no mention of rice. This also indicates that he was imprisoned in a remote tribe

where they probably used root flour, that too on occasions. The modium measure is

approximately a bushel or 15kg, not very much for a large palace kitchen, so it

must have been a smaller principality.

There is another aspect to be kept in mind. The train of the

Theban lawyer’s discourse is actually interrupted by Palladius and it is Palladius

who brings up a description of the Bissadae. The Theban lawyer himself does not

mention that he was with the Bissadae, it was an inference by Palladius.

The great king in Taprobane is another misnomer and does not

connect up to any event in Cheranaad or Tamilakam. Desanges connects it to the

Gupta era from the time of Samudragupta who he believes, was sovereign of both

Assam and of the Sinhala people. Though Ceylon was a tributary of sorts, Samudragupta

was certainly not resident in Ceylon. Derrett believes it was a Pandyan emperor

who was temporarily resident in Ceylon. Weerakkody explains that a ruler named

Pandu did indeed attack Lanka in the 5th century (not the 4th)

and he slayed the king of Sri Lanka to assume sovereignty. He adds - The

Mahavamsa calls him a Tamil (Damila), and later Sinhala traditions call him a

Cola. But his name suggests Pandyan nationality.

But then again, there was another connection between a king of

Lanka and Malabar, during the Chera rule dating to a couple of centuries

earlier. We have knowledge of a certain king called Gajabahu, often identified

with Gajabahu, king of Sri Lanka (2nd century CE), who was present at the

Pattini festival at Vanchi. But for one of them to get involved in the release

of a Roman Egyptian lawyer confined in a hill tribe is very strange. Nevertheless

it is not an easy connection for one to come up with, so should have been a real

happening. But what if a Chera King was temporarily resident in Lanka at that

time? It could be so, though there is only an obtuse possibility reinforced by

the use of the ancient term Cherantivu for Lanka (Lanka was known as

"Cerantivu' - island of the Cera kings).

That the lawyer strayed into remote territory is clear for

there was a presence of Romans not only in the Muziris region, but also near

Puhar on the East coast, if at all it was on the other side. His release after

six years thus becomes somewhat of a mystery and we have no record of his

return home. What could have happened is that a local king sent his emissary to

check and had the tribal leader flayed, and the prisoner released.

The lawyer was obviously distraught, and dropped his plans to

travel to Taprobane. While one could question in retrospect if such a travel did

indeed take place or if such a character existed, most accademics are clear

that the language and wording of the original text signify that they did. Perhaps

the connection to Taprobane could have been added by Palladius since he must

have had some vested interest in suggesting prospective trade links to

Taprobane. This story alludes to a potential Roman friendly king who lived

there, or for that matter a king who feared Romans and would submit to them.

I should also add here that the entire work of Palladius was

actually a submission to somebody much higher up, so Palladius must have been

trying to point out that Taparobane is a place to consider for future trade! It

is also to be recalled that the Romans were spending a lot of bullion on the

India trade and any possibility of cost reduction would have been of interest.

Then again, the entire work of Palladius is in two parts

with the first part detailing the Theban lawyer’s voyage was actually setting the

stage – explaining the voyage, the risks and the terrain etc and leading on to the

second part which covers the Brahmans of India, their ways and philosophy.

A keen reader might ask – How come the Romans, who had dared

to endure the rigors and perils of a long voyage to South India, never

continued their ventures to Ceylon? The obvious explanation has always been

that the South Indian kingdoms effectually prevented and prohibited western

merchants from trading directly with the island. But it is also possible that

the Romans did not feel the need to go all the way to Sri Lanka as long as its

products could be obtained easily and abundantly in the marts of India.

Weerakkody actually comes up with a plausible explanation and

points to the 5th century Pandu period - The rise of the Sassanids in Persia and the revival of trade under the

Byzantine emperors was matched by the growth in prosperity of Southern China,

which now began to increasingly demand the luxury articles that came from the

West by sea. Meanwhile, the Western Roman Empire became increasingly harassed

by the barbarian invasions. There grew a fresh demand for pearls, spices, and

precious stones. The South Indian merchants, who traditionally supplied these commodities

to the western merchants, or rather their Axumite middlemen, must have been

pressed increasingly for supplies; and it is natural that they should have

taken to exploring and exploiting fresh sources. It is probably here that one should

look for the background and the purpose of the occupation of Sri Lanka by Pandu

and his successors in the mid fifth century A. D. The invaders ruled from

Anuradhapura, but their interests penetrated far beyond the northern kingdom.

Derrett’s conclusion is that this was a commercial reconnaissance

venture which went wrong. He suggests that the Theban's mission, a commercial

reconnaissance, met with reactions on the

part of the Axumites amounting to non-cooperation, and on the part of Malabar

to downright hostility, preventing his entry into Sri Lanka, which was now

becoming a rich entrepot for spices, and resulting in his six year captivity.

The king in control of Malabar and Sri Lanka (whom Dérrett assumes to be a

Pandya, despite his fourth-century dating of the episode) ordered the Theban's

release and the severe punishment of his captor, a local sub-king, from a

desire not to disturb relations with Rome and the commercial advantages that

had accrued therefrom.

Or it could all be as Beverly Berg muses - No Greek traveler to India came back without

a few tall tales, and the Theban scholasticus is no exception. The story of his

capture and six years of slavery, working for the local king, is charming and

sounds genuine in its simplicity, but captivity was a common romantic motif of

the period. The scholasticus may have twisted his experiences a good deal to

give his story a romantic plot somewhat like that of Iamboulos islands of the

Sun story….

All of this took us back to a time when travel was risky and

hugely adventurous. Today the world is at your fingertip, virtually on the

computer screen. More developments will come by to make it all even more

realistic, but I can assure you that it will be nowhere near what these

pioneers experienced. No knowing what was to come, not knowing where you were going,

not knowing what to expect and then at the end coming back to narrate that tale

to wild eyed listeners. And that is why I love travel and travel a lot….

References

The Theban Scholasticus and Malabar in c. 355-60: J. Duncan

M. Derrett, Journal of the American Oriental Society.

D'axoum à l'assam, aux portes de la chine: le voyage du scholasticus

de thèbes (entre 360et 500 après j.c.). Jehan Desanges

Adventures of a Theban lawyer on his way to Sri Lanka: D. P.

M. Weerakkody

The letter of Palladius on India: Beverly Berg

Taprobane - D. P. M. Weerakkody

Sri Lanka and the Roman Empire - D. P. M. Weerakkody

Related blogs (click on text to get to the article)